Scry, To

This is going to be a long one, so if you’re looking for a tl;dr, here it is:

- I’m starting a video series to accompany this devlog. The pilot episode is here.

- There’s a new in-dev build available on all platforms here.

Last November, a little over a month after Super Win had launched and well after its initial sales spike had fallen off, I wrote a blog on Gamasutra describing its launch as a failure for which I theorized a number of possible causes. That was months before SteamSpy would emerge, and my closest point of reference was Eldritch, released a year earlier and under somewhat different circumstances. Knowing what I know now, I would say Super Win‘s reception was disappointing, certainly, but not necessarily worse than I could reasonably expect, having seen estimated data for other similar titles. It’s getting harder for any game to thrive in the current market, much less a one-developer pixel art platformer.

Of course, launch isn’t the end of the story; I’ve continued to support Super Win with new content since its release, and it’s had some moderate success during Steam sales. But it hasn’t yet recouped its costs, and it’s unclear whether it will. And that raises the question of how I can help ensure that Gunmetal Arcadia can and will. I’ve pointed to marketing as my biggest failing on Super Win before, and to some extent, I think that’s accurate, but it also wasn’t a game that lent itself well to promotion. It was a good game, and I’m proud of it, but I’d be hard pressed to say why it works in a sentence or two. That’s one of the problems I’m hoping to address with Gunmetal Arcadia. It has a very clear — and hopefully very strong — promise: “Zelda II as a roguelike.” I can dress it up a little more, describe the narrative conceits of conflicting factions uniting (or not) in the face of war, or elaborate on exactly how many -likes I’ve abstracted the design from the Berlin Interpretation, but the crux of it, the thing that’s always been exciting to me, is just that: “Zelda II as a roguelike.”

So that’s one vector along which I hope I’ve improved and can continue to improve. Another is visibility. I was needlessly secretive during the development of Super Win. A few #screenshotsaturdays here and there, some playtest sessions that only a small number of regional gamers could even have had the opportunity to attend, and then I was surprised when the reaction was muted? That’s what prompted me to start maintaining this devlog — that and the fact that I’ve always enjoyed writing about what I do. But I can do more. When I think about what visibility means in this era, it’s about having a wealth of content across a variety of formats, something for everyone to discover and share. So here’s what I’ve been thinking.

Development streaming feels like a decent option for improving visibility; it’s live, it’s personal, it’s sort of interactive, and more than anything I could write on this blog, more than any videos or GIFs I could post, it’s the clearest window into what game development actually entails on a day-to-day basis. The downside, and the reason I’ve been reticent to stream more often, is that I feel like I need to have at least a bit of an outline of a plan for what I’d be streaming, and many days, I simply don’t. I think with a little time and effort, I could make this a part of my normal schedule, but I’m not there yet.

So streaming may have to wait, but something I’m hoping to start doing very soon is producing a weekly video log to accompany or augment this weekly devlog. Sometimes it’s difficult to put into words (or screenshots, or even animated GIFs) some parts of the development process, and I think a video format could be a perfect accompaniment to the written word. Exactly what format these would take remains to be seen, but I would imagine it would fall somewhere on the spectrum between talking at my webcam and a slick documentary-style format. I’ve put together a sample of what this might look like here:

This first pilot episode is mostly focused on the introduction of the video log as an alternate form of development documentation and elaborates on some of my thoughts on where it could go in the future, as well as some of the other concepts I’ve detailed in this blog. I have more video content in the works, but I’d love to hear your feedback on this format and what sort of content you’d like to see. I’ll also be trying to answer questions in the video log, so if there’s anything you’d like to know about Gunmetal Arcadia, Super Win the Game, Minor Key Games, or anything else, please leave a comment on YouTube or get in touch on Twitter or ask.fm!

I’ve been thinking about the “Game Feel” test build I released back in March and how I haven’t done another one since. That void, coupled with the improvements I’ve been making to my Mac and Linux build process, got me thinking about possibly getting into the rhythm of publishing weekly in-dev builds. These wouldn’t necessarily be polished, consumer-ready pieces of software; they would literally be whatever state the game were in at the time, and it’s easy to imagine that week-on-week changes might be miniscule at best, but these builds could be another facet — importantly, a fully interactive one — of this transparent, documented development process that I’m envisioning.

So on that note, here’s the current build of Gunmetal Arcadia:

Weekly builds, June 15, 2015:

Windows: GunArc_Install.exe

Mac OS X: GunArc.dmg

Linux: GunArc.tar.gz

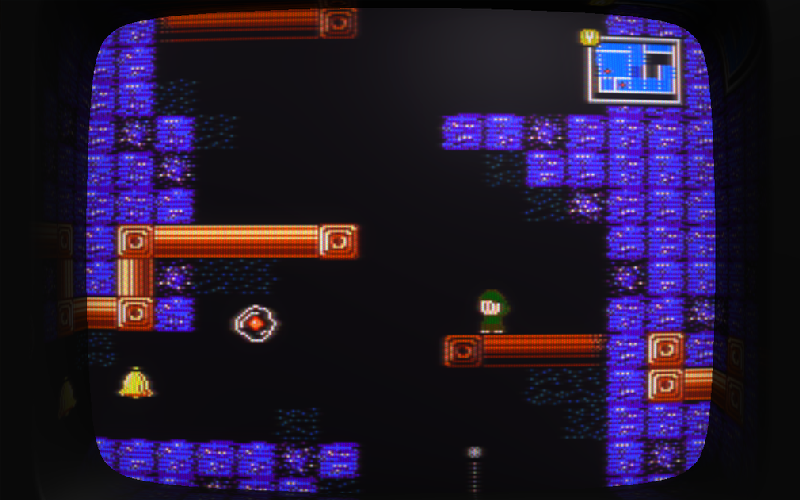

You may notice the game hasn’t changed appreciably since the last build I uploaded. You may also notice there are some obvious bugs — enemies not moving, getting stuck when falling down bottomless pits, and so on. That’s normal. That’s going to be the shape of these builds. These aren’t polished, tested, consumer products; they’re weekly snapshots of the development process, warts and all.

Community involvement in the development process is something that’s probably further off, once I have a more fully realized version of Gunmetal Arcadia and can start soliciting feedback on the complete game experience rather than specific aspects. From very early in this game’s lifecycle, I’ve been thinking that if there were ever a game I made that seemed perfectly suited for Early Access, it’s this one. As I’ve mentioned before, if I were to go down that road, it would only be once the game were believably at a place where it could be shipped — playable start to finish, feature- and content-complete for the current scope, and free of known bugs. That would be the ideal point at which to start involving the community in the process of tuning the game, adding, removing, or altering content as necessary, and shaping it into something better than it could otherwise be.

It’s an exciting vision, for sure. It also might be unfeasible. I already lose about half a day each week to this devlog. Once I start factoring in time spent on video editing, building deliverables on all platforms, planning out work ahead of time that I can cover in a stream, and so on, that’s sounding like a fairly sizable chunk of my week. I’m not sure I can afford to do that, or at least not all of it, or at least not all at once. But I think the benefits could vastly outweight the costs. So my idea is to start with what I can do. Test the waters. Make a video log. Publish an in-dev build. Do a development stream. See whether I can accomplish any of these in a reasonable amount of time and to a reasonable level of quality, and whether they’re effective in raising awareness. See whether this idea is worth pursuing at all. And if it is…well, there’s options.

Don’t worry, this blog doesn’t end with, “…and that’s why I have a Patreon now, so go pledge your support!” But, yeah. That’s one idea.

In the past, I’ve avoided the notion of using Kickstarter to fund the development of either Super Win or Gunmetal Arcadia, and I don’t have any intent or desire to go that way. I’m not in a position where I need those funds, and to be totally honest, I have some doubts as to whether I could run a successful campaign, regardless of whether I asked for the actual cost of remaining development. (And as we’ve seen in recent articles, that rarely happens, thanks to a perpetuating cycle of misleadingly low estimates lowering consumer expectations of costs and vice-versa.)

But a Patreon campaign, not to fund the development of the game itself, but to help mitigate the recurring costs of sustaining what I want to believe could be an unprecedented degree of openness and transparency about the development of the game? That’s something I might be able to get behind. It’s easy to imagine what rewards for a campaign like that could be. Your name in the credits (that’s one I always like as both a player and developer), a free copy of the game when it launches, and so on.

I’m not saying any of this will definitely happen, but these are a few possibilities I’ve been kicking around for where Gunmetal might go in the future. I’m curious to hear your thoughts.

Support Structures

I had a totally different blog drafted and ready to go this week — one that I’m very excited about, so watch for that next time! — but I thought it would be nice to bookend the last two months of side project work by doing a bit of a recap here instead.

Two months.

Two months to build five new levels, implement a mapping system to be displayed in two different modes, automate the process of calculating the number of collectables in each level, define what a level even is in the context of this mapping feature and having built the game worlds in totally incongruous ways, implement a speedrun mode with powerups that are maintained separately from the ones you can find in the normal campaign, add a speed boost powerup, track position data over time and visualize it as a player “ghost,” implement Steam leaderboard support and a leaderboard UI, write some new dialog, append some new music to the soundtrack, find and fix bugs, and deploy six builds across three storefronts.

That’s a lot to get done in two months, and it’s been a bit of a rough landing, requiring several days of hurried bug fixing. But it’s all wrapped up now, fingers crossed, and Super Win the Game can go back to being a thing that I support from a distance rather than with hands-on development.

My plan with this update was to effectively “relaunch” the game and give it another shot at visibility and viability. Even though a few of my ideas fell through (for instance, a relaunch discount was forced off the table due to the timing of other sales), some unexpected opportunities popped up to take their place, and ultimately it does feel like I’ve been successful in drumming up renewed interest. It’s difficult to say whether it will be enough to justify the costs, but it’s off to a pretty good start, and I’m hopeful about the future.

It’s coincidental that this update/relaunch landed so close to the release of David’s NEON STRUCT, and I’m not entirely sure what that means for messaging. One of our goals when we formed Minor Key Games was to benefit from the promotion and visibility of each other’s titles. It’s possible this is a case for that. On the other hand, it feels like maybe I’m diluting a message that should be taking precedence. I don’t have enough knowledge, experience, or data to support either side at this time, but it’s something I’m thinking about.

I can’t wait to get back to Gunmetal Arcadia, and I’m super excited about some of the new developments I have in the pipeline. But it’s been nice to revisit Super Win and right some of its wrongs. As I said two months ago when I first announced this update, I had had a lot of bad feelings about this game for a while after its launch, and I think I’ve finally managed to put those behind me. If you haven’t played it yet, I’d encourage you to give it a try. The minimap really does make a world of difference; everyone who asked for it was right, and I’m glad I finally reached a point where I wasn’t too proud or too burnt out to consider it seriously.

Super Win the Game is available for Windows, Mac OS X, and Linux for $7.99 (standard) or $9.99 (soundtrack edition). You can find it on Steam, Humble, and itch.io. The soundtrack is also available for purchase on BandCamp.

Remaining Cross-Platform

Last February, I wrote on my personal blog about the difficulties I had encountered in porting my engine from Windows to Mac and Linux. Since then, I’ve continued to iterate on these versions, and I thought I’d share some of the experiences I’ve had in that time.

When I completed the first iteration of this work last year, I was only building a 64-bit Linux binary. The reason for this was simple: I had installed the recommended Ubuntu distro for my PC. This was a 64-bit distro, which meant that by default, I was building 64-bit applications. Based on what limited data I had available from, e.g., Steam and Unity surveys, this seemed like a safe bet, but I very quickly heard from 32-bit Linux users who were unhappy with this decision. At the time, the only cross-platform game I had shipped was freeware, so I wasn’t too concerned about it, but I knew that I would probably have to cross that bridge before shipping Super Win the Game.

In June, after four or five months of Windows-only development, I began compiling Super Win on Mac and Linux. Right off the bat, I ran into some bugs in my OpenGL implementation that had never appeared in either my Windows OpenGL build or in any version of YHtWtG. Both of these were my own fault, and one was easily fixed (I was calculating the size of vertex elements incorrectly in certain cases), but the other was a little more sinister. I had some shader code containing a parameter which was intended to be a float but had been written as a float4. Outside of its declaration, all the code both within the shader and in the game’s code treated it as a one-component float. Despite being technically incorrect, this worked just fine on Windows under both DirectX and OpenGL. It was only when I switched to Linux and ran the game that the GLSL compiler on that platform threw a fit about it. In retrospect, it’s possible that testing with debug D3D and higher warning levels might have caught this far earlier, but I rarely remember to test in those conditions unless I have an obvious rendering bug in Direct3D. The scary part is that, even having found and fixed this one particular bug, I don’t feel like I can be entirely certain that my auto-generated GLSL code will compile on all users’ machines, and in fact, evidence has suggested that it will not, for reasons that aren’t yet clear to me.

It was around this time that I made the first of three attempts to build 32-bit binaries on Linux. Each of these deserves its own paragraph.

My first attempt involved building a 32-bit binary on my existing 64-bit distro. It sounded simple enough: add the “-m32” flag when compiling. What could possibly go wrong? Of course, this also meant recompiling 32-bit versions of all the libraries I was linking (SDL, Steam, GLEW), and of course each of these had their own dependencies. This led to what I described on Twitter as a Mandelbrot fractal of dependency issues. A zillion sudo apt-get installs later, I reached a point where (1) I still didn’t have all the dependencies I would need to compile 32-bit binaries, and (2) Code::Blocks would no longer open because some of the dependencies I installed had broken compatibility. With no clear path to revert these changes, I began manually removing these dependencies and reinstalling the 64-bit versions where I could. I finally reached a point where Code::Blocks would open again and I could compile the code, but it would immediately crash. Then I restarted my PC, and Ubuntu simply would not boot up. I had killed my first Linux distro.

This was June 2014. I had first installed Ubuntu on my PC eight months earlier, and I didn’t really remember how the process had worked. Did I use Wubi? Did I create a partition? There seemed to be several ways this could work, and none of them was wanting to play nice for reasons I couldn’t fathom. Sometimes my PC just wouldn’t boot to Ubuntu. At least once, the Ubuntu setup install process just spun indefinitely until I had to power my machine down. I think I restarted the entire process at least five or six times that night. Eventually, I ended up getting a 32-bit distro installed, in the hopes that I could build a 32-bit binary natively and it would just work on 64-bit distros, too. I was able to produce a 32-bit binary, but it didn’t run on a 64-bit distro right off the bat. I started installing dependencies to see whether I could make it work, and…yep. I killed that distro, too. Two Linux distros dead in two days.

Now here’s the really fun part. At some point when I was trying to get any version of Ubuntu working again, I ended up with my PC booting to GNU GRUB by default rather than the Windows Boot Manager that I was familiar with. And now that my Linux install was dead, GRUB wasn’t working, either. My PC wouldn’t boot at all, not even to Windows. For all intents and purposes, it appeared I had just bricked my PC trying to install compatibility packages on Linux. In an era before smartphones, that probably would have been true. Fortunately, I found a StackExchange post that described the exact problem I was having and the solution. I had a brief moment of panic when I wasn’t sure if I even still had my Windows discs, but I did eventually find them and was able to repair the damage. I had lost three days and could still only build 64-bit Linux binaries with any reliability, but I didn’t lose my PC completely. I chose to ignore the problem and get back to game dev work for a while.

A month later, barely a day after wrapping up three weekends in a row presenting the game at various expos and conventions, I returned to the wonderful world of Linux development with a new plan of attack. Since my desktop PC was too scarred from previous failures and I didn’t trust it to stand up to a fresh install, I decided to turn my laptop into my primary Linux development environment. This time, I went with a Wubi install, despite recommendations to the contrary — it was, I had eventually learned, how I had installed Ubuntu the first time, when I had had the least trouble with stability. I installed a 32-bit distro, rebuilt all my external libraries, compiled the game, and tested it on my 64-bit desktop install, and…this time it worked.

I can’t explain that. I don’t know why my results were different this time. To my recollection, I had followed the exact same steps once before with different results. I tested it on my Steam Machine and it worked there, too. To date, I don’t believe I’ve had any complaints about 32-bit/64-bit compatibility since I started building in this environment. I’m happy it finally worked, and it was strange how smoothly the process went this time compared to all my previous attempts, but I can’t explain it. In all likelihood, if this environment ever fails me for any reason, it will be the death knell for my support of Linux.

I’ve been using various versions of Visual Studio as my primary IDE since 2005. It took me months, if not years, to feel totally comfortable with it, so it’s not surprising that working in other environments would present difficulties.

I use Code::Blocks on Linux and Xcode on Mac. Code::Blocks seems like it was designed to be familiar to VS users. It has some oddities, but there are usually pretty clear analogues between the two environments. Importing projects and configurations from VS was fairly uneventful; it’s been the little unexpected things that I’ve had to learn to deal with in Code::Blocks. For instance, the order in which library dependencies are specified matters in C::B where it doesn’t in VS. This gave me endless linker errors, and for many months before I understood the source of the problem, I just worked around it by making throwaway calls to various library functions in game code so that the linker would understand it needed to link those libraries. I had another issue for a while where Code::Blocks would eventually just sort of choke and slow to a crawl after compiling the game once or twice. This turned out to be related to the inordinate amount of warnings being displayed in the output window. Simply lowering the warning level fixed this problem. (Yes, a pedant might insist that the real solution here would be to address the warnings, but I always compile with /W4 in Visual Studio and produce no warnings at all, so I say gcc is just too persnickety.) The Code::Blocks debugger has been fairly hit-or-miss for me, too, often ignoring breakpoints entirely and requiring me to break at other places and step through code to get to where I want to be. I suspect but haven’t proven this may be related to spaces in filename paths, which is one of those fun “I’ll know better the next time I write an engine from scratch” issues that crops up from time to time.

Xcode is a totally different ball of wax. It wants to work its own way with no regard for what others are doing. In my experience, it’s also a little too eager to happily build and run projects that really aren’t configured correctly, whch has made it difficult to know for sure whether the applications I’m shipping will actually work on other users’ machines. It also likes to put intermediate and product files in bizarrely named folders buried somewhere inaccessible, and the options to relocate these paths to something more intuitive aren’t readily apparent. Shipping a product on Mac is a strange thing, too; Xcode really, really wants every application to be built for and deployed to the App Store, and that’s completely orthogonal to what I’m doing. As a result, the builds I produce outside of Steam are shipped in compressed disk images, which seems to be de rigueur despite the fact that OS X will spit out warnings about downloadable apps shipped this way. It’s a strange situation, where Apple seems to want all apps to go through the App Store with no regard for cases in which the App Store simply doesn’t apply.

As I’ve been wrapping up the upcoming Super Win update, I’ve found myself in a familiar scenario of having to make new builds fairly frequently as I find and fix bugs. On Windows, deploying a new build is fast. I have a single script that rebuilds all game content, compiles Steam and non-Steam builds, builds an installer, and automatically commits all changes to source control. Historically, rebuilding on Mac and Linux has always been a little more involved, as I have not had comparable scripts, and have instead had to manual open each IDE, choose the appropriate configurations or schemes, build the game twice (once for Steam and once for non-Steam), and manually package the executable and content into a .tar.gz or .dmg.

Yesterday, after repeating this process two or three times in as many days, I finally decided it was time to automate this process. As it turns out, both Code::Blocks and Xcode have fairly simple command line support, as do tar and hdiutil for assembling the compressed packages. A few hours’ work later, I have scripts that will quickly and easily produce iterative builds on each platform. There’s still a little more work I could do here to achieve parity with my Windows build script (e.g., automatically commiting to source control), but it’s a good start that should save me some time in the long run.

What would be really cool, and I’ll have to give this one some thought to work out the details, would be if I could automatically update the Code::Blocks and Xcode projects whenever my Visual Studio projects change. Most of the time, this happens when I’ve added, removed, moved, or renamed files. Assuming C::B and XC both have support for modifying projects from the command line (and that is admittedly a big assumption to make without researching it at all), I can imagine I could write a script to watch for changes to the VS project and make the corresponding changes in the other IDEs.

At the moment, I only build on Mac and Linux every once in a while during core development, so keeping the projects in sync isn’t a huge hassle to do by hand. One of my potential goals for the future, however, is to start producing more frequent in-dev builds on all platforms, and at that point, this might become a bigger deal.

Sleep and What We Are

I hope everyone is having a good Memorial Day weekend! As there’s no rest for the wicked (and money doesn’t grow on trees), I’ve been working a bit, trying to wrap up the new Super Win content, fix whatever bugs may still be lingering, and hopefully make some improvements to perf and stability while I’m in there.

In case you missed it, our latest game NEON STRUCT came out last Wednesday. Since it’s David’s game, I’ll let him talk more about its reception when it’s time, but I will say it’s interesting to watch how it’s been trending relative to both Eldritch and Super Win, especially in light of the amount of mainstream coverage each game has received. It certainly calls into question some of the ideas I’ve had about how to approach Gunmetal‘s launch when that time comes.

I’m 99% done with the speedrun courses for Super Win. On Saturday night, I took about three hours and did a complete playthrough of the game looking for bugs in the minimap system or speedrun courses. There’s still a lot of stuff left to fix, and a few unsolved problems with regards to how to treat certain secret areas on the map. I’ve been aiming for the end of May or start of June for a launch date (June 1 in particular has been my ideal target), and I believe I’m still on track to hit that date, but in light of some other obligations and circumstances (which for one reason or another I can’t elaborate on here), I’ve been leaning towards either delaying this update or decoupling it from the price drop. I still have a little while to figure this out, so we’ll see which way it goes.

This week has been strange in that I’ve spent a lot of time working on various programming tasks which I’ve ended up reverting. I’ve had an idea for while to try to add support for a callback system that would use (non-static) member function pointers and a target object to circumvent a common pattern that I find myself running into in which I have to make a callback to a static function, passing in the target object as a parameter and then running a function on it. Although this feels like a simple process on the surface, C++’s handling of member function pointers makes it somewhat difficult. The crux of it is that member function pointers are typed differently depending on the class they belong to, which means that, barring any sort of trickery, the thing that makes the callback needs to know the class of the thing that receives the callback, and that defeats the purposes of the system, which is to be flexible and generic; the caller shouldn’t need to know anything about the callee. I prototyped an initial implementation of this a few weeks ago before going on vacation to Nebraska, rejected that version, and recently came back to the problem, believing I’d found a solution. After a few days of off-and-on work, though, I’m not really sure there’s a way to do exactly what I’m trying here, and in the absence of a really strong need for such a feature, it’s probably not worth pursuing further.

I had another similar experience this weekend. I ran into a case where it felt like it would be nice to be able to chain together any number of fullscreen postprocess effects, each a separate draw call, without having to set up the corresponding data in my render pipeline, which has historically been cumbersome to deal with when draw calls must happen in a specific order, as these would. The trouble in this case is that my renderer has been very specifically built to perform optimally in one way, and circumventing that behavior to make it act differently without breaking or losing the perf gains of the normal path turns out to be a rabbit hole of special case behavior. Eventually, I spending a few hours poking around in this code, I had to ask myself whether the motivation was strong enough, and in this case, it wasn’t. So I reverted that work.

I’ve had to discard or roll back work before, but it is unusual that I’ve had cases like these in such rapid succession. I think I’m itching to get back to work on core features after spending a couple weeks doing primarily content creation work on Super Win. That work just isn’t as satisfying, and it’s also weirdly emotionally draining. Even after just a week or two or level building and writing for Super Win, I’m already starting to feel the funk that loomed over the last few months of development on the original release. I’m hoping the procedural content generation scheme and loftier game systems design I have planned for Gunmetal will help stave off that mood, since it means I should be spending more time in code and less time building content that might only be seen once.

A Tendency to Dream

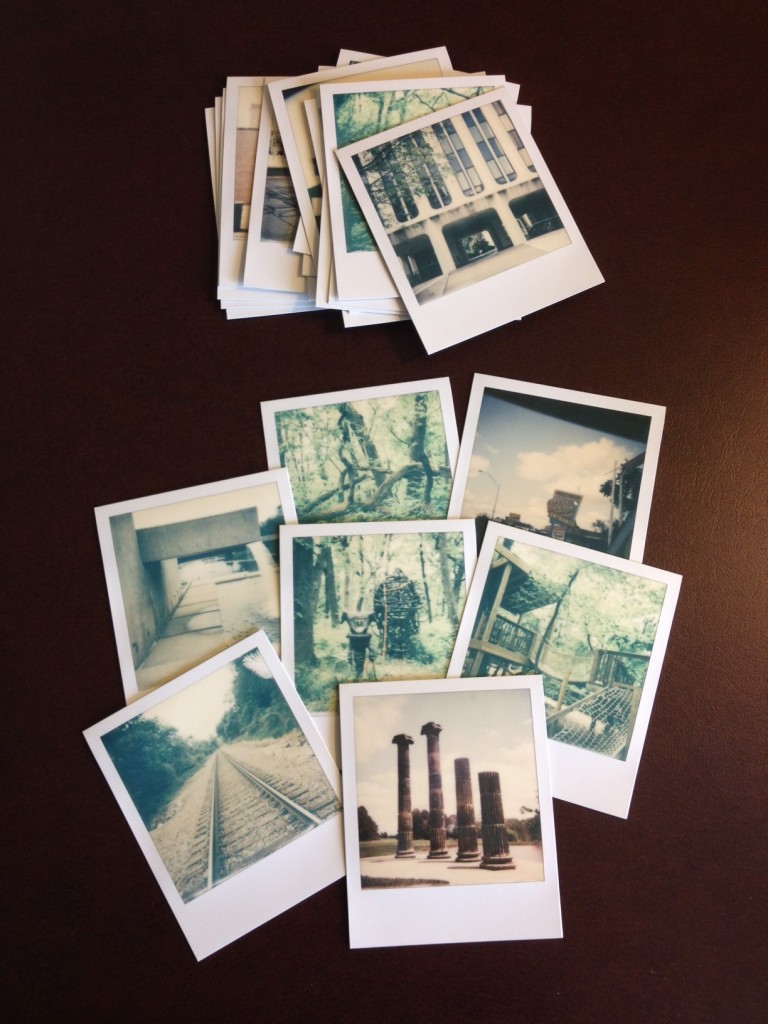

Last week’s mystery Polaroids are courtesy of a week David and I spent on the road visiting Lincoln and Omaha, Nebraska. It’s been ten years since we graduated from UNL, and it felt like a good time to see how the cities have changed, visit some old haunts, and mostly be glad that I don’t have to worry about classes and grades anymore.

I’m continuing to make progress on Super Win speedrun courses. Three of the five courses have been fully grayboxed and need to be tweaked and arted up. One is in the process of being grayboxed, and the last one I haven’t started building at all yet.

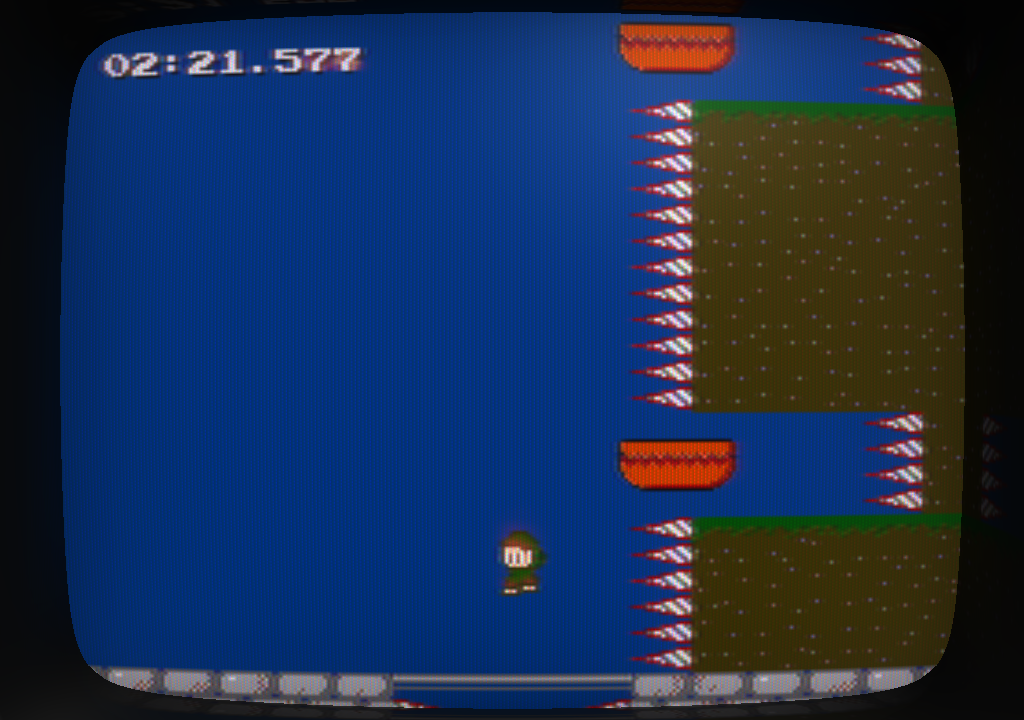

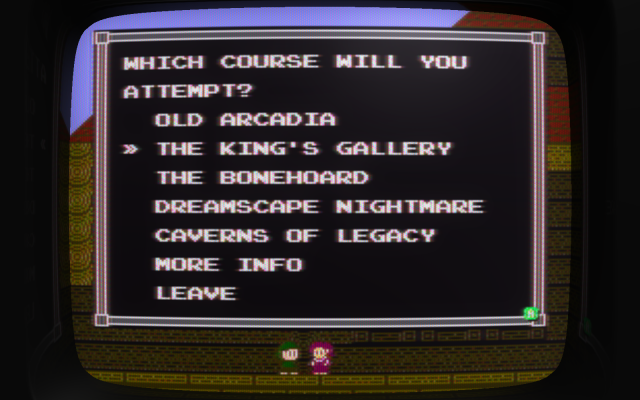

The first course is Old Arcadia. This course requires some long jumps and wall climbing that are only possible with the new coffee cup powerup, which grants a temporary speed boost.

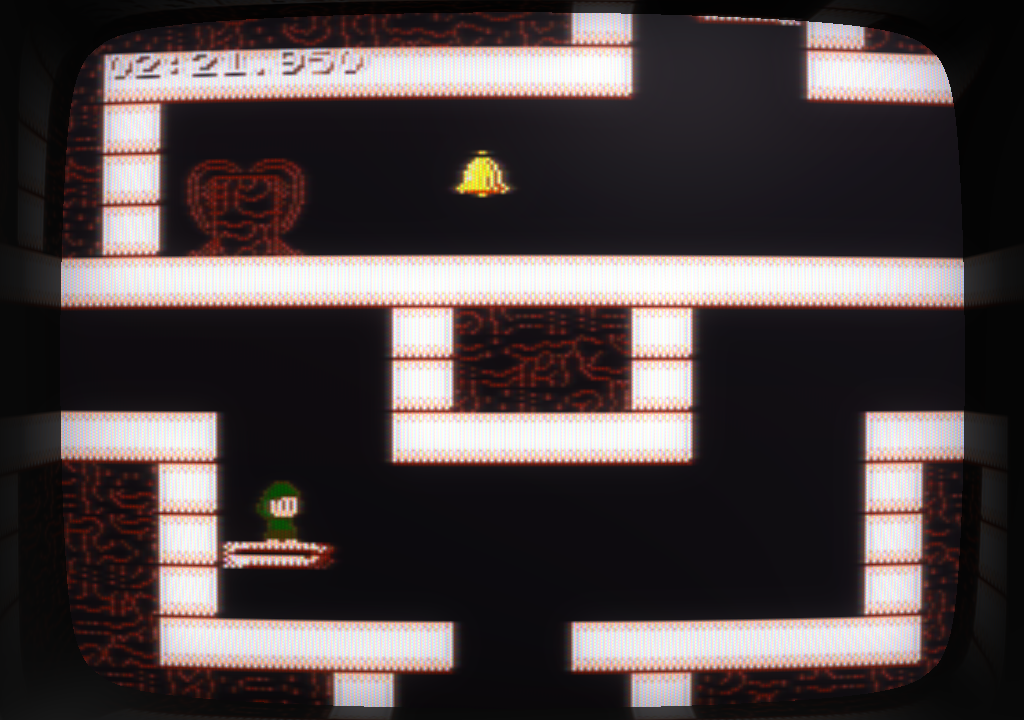

The next course is the Bonehoard. If you’ve finished the campaign, you’ll recognize this tileset from one of the last areas of the game. There are a couple of branching paths throughout this course; the trick will be figuring out which one is the fastest.

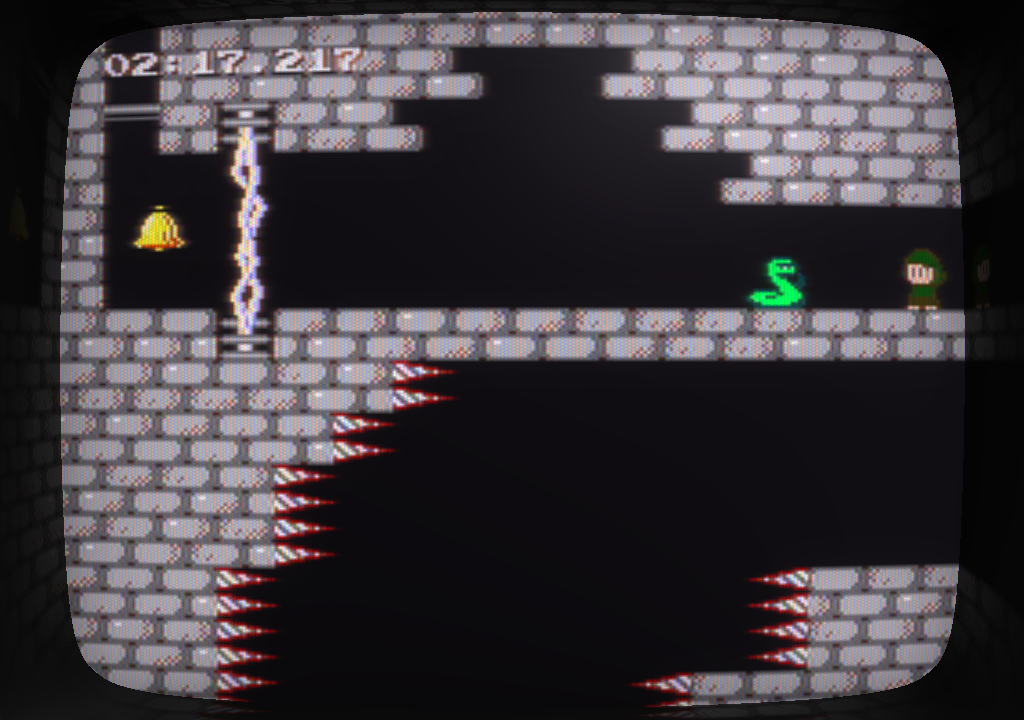

The Dreamscape Nightmare course winds back and forth around a central tower. You’ll have to climb to the pinnacle to find the gear you need to plummet back down to the bottom and reach your goal.

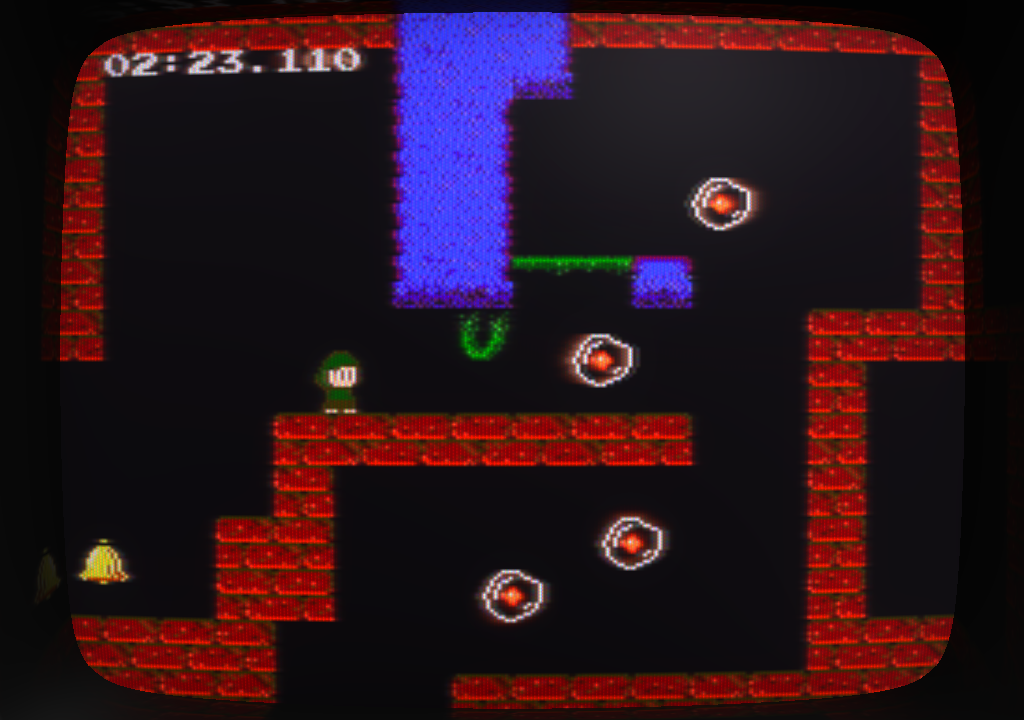

The Caverns of Legacy will be familiar to fans of the original You Have to Win the Game. This course contains reworked versions of some iconic rooms from that game. This has been an interesting challenge on account of the difference in scale between the two games. I rely almost entirely on 16×16 tiles in Super Win, and coupled with the narrower dimensions (256 pixels across vs 320 in You Have to Win), I’m having to simplify the geometry of these rooms and try to evoke the originals rather than rebuild them 1:1.

Finally, there’s the King’s Gallery, which isn’t pictured here because I have yet to start building it. My idea is to play around with the concept of traversing the outside of a space that was previously encountered, a sort of deliberate breaking out of the world. It’s an idea I’ve had at the back of my mind since the first YHtWtG, but I’ve never really explored it. Hopefully it’ll turn out how I’m imagining.

Hey, remember these flyers I did for Super Win that were designed to look like an original NES “black box” release? I’m working on something similar for Gunmetal Arcadia, this time in the vein of ’90s video game ads — white backdrop, serif font, etc. This is obviously still a pretty early mockup, but it’s a good example of the sort of thing I’m going for.

Reusing the same MIDI-to-proprietary-synth tech in Gunmetal Arcadia as I did in Super Win the Game has put me in a good place to be able to write music off and on for the entire duration of the project rather than having to worry about composing a whole soundtrack all at once close to launch. I’ve already written easily 50% more music for this game than I did for Super Win, and I plan to keep on writing as long as the melodies keep coming to me. Here are a couple of the more recent tunes I’ve written.

I guess this next bit might not be super interesting to non-devs, but since I like to talk about some of the aspects of development that sometimes go unnoticed, here’s a fun thing that happened. While I was out of town, a thunderstorm took out my modem/router. For some reason, this was the one device that wasn’t behind a surge protector, so I guess that’s what I get. To their credit, my ISP replaced it immediately, no questions asked, although I also had to put a new ethernet card in my PC because apparently the surge also blew out the ethernet port on my motherboard.

Anyway, the point is, along with a new modem and router came a new IP address. That’s nothing new; when I was living at my previous apartment and using a different ISP, my IP address would change at least once a year for no reason at all. It’s always been a minor irritant, though, because it means I need to update the URLs on all my local SVN working copies. (As I’ve discussed before, I keep each project in a separate repository, so I’ve ended up with quite a few working copies checked out.) Historically, I’ve always just dealt with this by relocating each working copy whenever I touch it next, but this time, I finally decided to simplify the process. I wrote a script to output the URL of each working copy in a given directory, and if its address differs from a provided target IP, it will automatically be relocated to the new one.

On the Road Again

Grab Bag 27

This week marks another special guest appearance from Super Win the Game. I know, I know, I want to go back to writing about Gunmetal Arcadia, but I’m full time on Super Win for now, so that’s what I’m covering. But hey, at least there’s a shiny new header image! I got the random urge to paint a scene from Gunmetal over the weekend, and that’s what I came up with.

Last week, I mentioned that I had prototyped attachment of player ghost data to leaderboard entries. This week, I wrapped up that work and implemented a leaderboard UI. Your fastest time will be recorded for each speedrun course. When playing offline or in non-Steam builds, you can view your own personal best times and race against your own ghost. When connected to Steam, you can view all players’ time and race against any other player’s ghost. All the usual Steam leaderboard modes (global rankings, personal ranking, and friends’ rankings) are supported.

I’m making slow but steady progress on the courses. Level design was one of the most tedious parts of making Super Win the first time around, and I’m definitely starting to feel that slog again, but I’m excited about the new challenges I’ve built. I sort of expected to feel like I had already done everything I could do with the content available, but I’m finding some interesting new ways to piece things together.

I’m continuing to support the anaglyph 3D mode going forward, so I fixed up the minimap to play nice with this feature. Depending on whether I foresee doing any more major updates for Super Win in the future, it may be worth refactoring this feature to clean up a lot of copy/paste code that exists across the codebase.

Last month, I updated Super Win to include a language option in the menu. The game only supports English by default, but additional languages can be added by players, and a Russian translation is currently available in the link above. I realized shortly after publishing this update that some strings which had already been retrieved in one language were not updating immediately after changing the language. In most cases, continuing to play as normal would fix the problem, and at worst, exiting and restarting the game would always fix it, but I wanted a real solution and not a workaround. To that end, I’ve written a language-sensitive interface that classes may implement if they need to respond to the game language being changed. So far, I’m only using this in one place, for updating key prompts that had already been cached, but in the event that more of these bugs pop up, I’ll have a better way of handling them in the future.

As I’ve been writing music for Gunmetal Arcadia, I’ve rejected a few pieces for sounding too much like they belong in Super Win. I want Gunmetal to have its own unique sound, and even though I’m reusing the same synthesizer tools I wrote last year, I’m trying to lean more on minor key melodies and weird, chaotic compositions. Not everything I’ve written has fit that bill, and a few tunes have been cut. But as I was thinking about new content I could add to this Super Win update, a couple of these felt like they’d be a perfect fit.

This short loop plays inside the Hall of Speedruns, located in the Town of Lakewood. This is where you can access the speedrun courses and view the leaderboards.

This is probably going to be the background music for the “Old Arcadia” course, or possibly one other that I haven’t started building yet. Or both. We’ll see. It’ll go somewhere.

This Wednesday marks the third birthday of the original You Have to Win the Game and one year since it landed on Steam. I poked around in the source code a day or two ago to remind myself what state it was in. Last June, as part of the neverending struggle to support a wider set of Linux installs, I attempted to merge in some then-recent engine changes and build a 32-bit executable. It failed, I rolled back the version on Steam, and ever since then, the code in my repository has been out of sync with any published version and not really in a good place to rebuild the game if I had to. So I finally took the opportunity to roll back some of the more problematic changes and at least get back to a state where I can build the game as it appears on Steam today. I don’t know whether that will go anywhere. A few months ago, I considered adding a Super Win upsell screen when starting or exiting the game, in essence to frame it as sort of a demo for Super Win, and I suppose this puts me in a better place to do that, but I’m still on the fence there. On the one hand, it’s kind of tacky. On the other hand, YHtWtG is about two orders of magnitude more successful than Super Win but doesn’t generate any revenue, so it feels like a wasted opportunity.

I’ll be out of town next week as David and I are taking a trip to Nebraska to gather ideas for a future title and visit our college on the ten-year anniversary of our graduation, but I’ll be sure to have something ready by next Monday, even if it’s just Polaroids from the road.

Maps and Ghosts

It’s been another week with a minimum of work on Gunmetal Arcadia, so today I’ll be covering the ongoing updates to Super Win the Game in greater depth.

For starters, I’ve added a highly-requested mapping feature to Super Win the Game. As in most Metroidvania titles, the map is automatically filled in by traversing the environment. Regions containing gems that have not yet been collected will be flagged on the map with a red dot. A minimap sits in the corner at all times and can be expanded to full size with the press of a button.

Initially, my hope was that I could automatically generate the map images from game data. I even got as far as prototyping an algorithm that would do a flood fill through the world looking for adjacent rooms and drawing the map as it went. Unfortunately, this was insufficient for a number of reasons. It was too slow to accurately determine rooms that the player could walk between; to do this, I would have needed to do a flood fill of each tile in every room, marking space as inside or outside the walls, in order to correctly identify paths between rooms. Furthermore, it would have been impossible for this algorithm to flag rooms as secret areas, as this decision is often based on context and not something that could be easily determined by examining a room algorithmically.

For these reasons, I’ve had to draw each map by hand. In fact, there are two versions of each map, one with secret areas revealed and one without. Once the player has traversed a secret area, the map will show this path, but until then, it may appear as a wall.

I was initially considering only showing the map within dungeons, but I’ve had to expand the scope for a variety of reasons. This decision was based on the fact that many areas of the game (towns, building interiors, various caves and forests accessible from the overworld map) are trivially small and don’t warrant a map, but as I began drawing maps, I realized some areas that I don’t technically consider dungeons — for instance, the icy lake outside the glacial palace, or the exterior facade of the desert ruins — could still benefit from having a map. The final nail in the coffin was the inclusion of gem markings on the map; once I knew for sure I would be supporting that feature, it pretty much meant I would need a map everywhere. The one exception is the dream sequences. These never contain gems, so I feel I can get away with not having a map during these sequences, and I think the exclusion of a map may help to further clarify the delineation between the real world and dreams.

One of the reasons I rejected a minimap when I was originally developing Super Win last year was because the game’s regions are not always logically represented by its map files. Many seemingly disparate locations may exist within the same map file, such as the tutorial, all dream sequences, and the hidden region within Subcon, or the interiors of many buildings across a few different towns. Likewise, some areas that are logically connected, such as the Lair of the Hollow King and the Hollow Heart at its conclusion, actually exist in separate map files. I knew that one of my first tasks would be solving this disparity. This involved tagging every map file or region with an identifying name.

Ultimately, I ended up breaking down maps into the smallest possible discrete regions, even when these are just a single room, as in the case of many building interiors. This decision led to another problem: once I began marking gems on the map, I found that I wanted to be able to see the total number of gems in a region, but the regions I had defined were too small to provide a meaningful count. To address this, I added another layer of markup to define regions that were part of the same larger logical space. In this way, I could keep track of, e.g., how many gems existed in a town, even when this space spanned multiple maps.

Calculating the number of gems within each region is done at runtime when the game starts up. This is a somewhat intensive process, as the contents of each room must be examined to see whether it contains any gems, whether those gems have been collected, and so on. In the future, once I’ve finished building the new speedrun courses and am certain that content is locked down, I may cache these results for faster loading, but in the event that I don’t, I’ve added a loading screen such that the game doesn’t appear to have crashed or frozen.

There is one remaining problem that I haven’t solved yet, and that is how to handle saved games that were made prior to this update. As it stands, the game would be loaded with no minimap data, so any rooms the player had already traversed would have to be revisited in order to fill in the map. As a partial fix-up, it would be easy to automatically fill in rooms from which the player had previously collected a gem, as I would know for sure they had been there already. Any further fix-ups would have to be guessed at, possibly by attempting to pathfind through the world from known visited rooms to known entry points. Alternatively, I might simply pop up a notification when loading an older saved game explaining that the minimap will not be filled in. We’ll see.

The second order of business is speedrun courses. This goes back to an idea I had early in the development of Super Win, but eventually the underworld region I had set aside for this purpose ended up becoming something of an epilogue to the main campaign instead, and I shelved the speedrun idea for a time.

I’m planning to have a number of speedrun courses, probably five or so, and these will be accessible from the Town of Lakewood right at the start of the game. Each speedrun course will prescribe its own set of gear, so the playing field will be level regardless of how far you’ve advanced in the campaign. You may also find familiar powerups on the course that will last for the duration of the run and will be forfeited upon its completion. Finally, I’ve added one new powerup: a coffee cup which provides a speed boost for a short duration.

I’m currently in the processing of grayboxing speedrun courses, and I’m pretty excited about the results so far. I’m aiming for difficult platformer challenges more in the vein of the original You Have to Win the Game. I also want to provide multiple paths through each course. My hope is that these paths will provide a good balance between difficulty and speed and incentivize repeated playthroughs in the interest of finding and perfecting the optimal path.

From the start, I knew that if I were implementing a speedrun feature, I would want ghosts, but it took some time to figure out a good implementation. I had previously implemented input recording for Gunmetal Arcadia as a solution for an attract mode and possibly for saving and replaying full game sessions. I ported this code back to Super Win, but it turned out not to be useful for ghosts, as wholesale input recording is only useful in the absence of ongoing player input. Eventually, I decided to implement this feature in the simplest way I could imagine, by saving off snapshots of the player’s position at regular intervals. I’m still playing around with the exact rate, but currently I take a snapshot every tenth of a second while the player is moving and also in response to significant events such as jumping, landing, wall hugging, dying, and respawning.

Ghost data is saved to file when the player finishes a speedrun course and chooses to overwrite their previous best time. This ghost data will automatically be replayed the next time the player enters that course, allowing the player to compare their current performance against their previous best.

The next step, and one that I’ve prototyped far enough to have confidence in being able to ship it, is to associate ghost data with online leaderboard scores such that players can choose to race against each other’s best results. Naturally, this feature will only be available for Steam players, but for non-Steam versions, local results can still be saved and replayed.

I don’t yet have a release date for this new content, but as I’ve mentioned previously, it will be available free of charge to all current players and will coincide with a relaunch of the game at a new lower price. Hopefully this will be sooner rather than later; I’m a little over three weeks into this work and itching to get back to Gunmetal Arcadia, but I also want to make sure this is a substantial piece of high-quality content, so I’m trying not to take any shortcuts or do anything halfway.

Meet Your Factions

One of the core promises of Gunmetal Arcadia since its announcement has been the idea of faction conflict. There are two major players in the realm of Arcadia, each with its own set of characteristics and values. As you play the game, the choices you make will affect your standing with each of these factions, and over the course of multiple sessions, the concatenation of previous outcomes will sway the narrative in different directions.

Let’s take a look at these groups and what each represents. But first, an introduction to the race you’ll be playing in Gunmetal Arcadia!

Tech elves are the native inhabitants of the land of Arcadia. They have an innate affinity for tools, technology, and weapons, and they also possess the ability to outfit themselves with biological augmentations.

Elves may choose to assist one of Arcadia’s factions, or they may remain unaligned. Each of these options comes with its own risks and rewards; factions can provide equipment and upgrades for their followers, but some citizens may respond negatively to members of an opposing faction or those who do not commit to any cause at all.

In the face of a greater threat, however, there is no open war between these factions. Whatever conflicts or tensions exist in that space must take a back seat to the duty of defending the land.

First up, we have the Gunmetal Vanguard.

The Vanguard stands for strength and honor. These brutish warriors value military might above all else. They pride themselves on crafting the finest weapons and armor in all the land.

Members of the Vanguard are well-versed in melee combat and prefer to approach combat situations directly, sword in hand.

As an unaligned tech elf, you may pledge your allegiance to the Vanguard and receive their sigil, the Vanguard’s Hammer. This item imbues its holder with great strength and constitution.

On the other side of the coin, we have the Seekers of Arcadia.

The Seekers represent knowledge and intellect. They are scientists and engineers, keenly interested in understanding, manipulating, and augmenting the inner workings of all things.

Acolytes of the Seekers prefer to analyze combat encounters and choose the smartest approach from all available options.

A neutral tech elf who choses to be allied with the Seekers will be granted their sigil, the Lens of the Seekers. This item amplifies the abilities and stats of its wearer.

In the future, I hope to do more of these short lore posts — this week, my return to Super Win necessitated it, but it also aligned with some writing and narrative development I’ve been doing as I start planning promotional material for future events. Maybe next time I’ll take a look at the rogues gallery of the Unmade Empire, the primary antagonists of Gunmetal Arcadia.