A year ago tomorrow, I launched this Gunmetal Arcadia development blog. Two days later, I released my first commercial indie title, Super Win the Game. I had been thinking about covering these in separate blog posts, but there would probably be so much overlap between the two that I might as well roll them both into a look back at the last year. This is going to be long and kind of rambly, so if you’re looking for a tl;dr, I guess it would be this: “I’m still making games.”

As I discussed in a two-month postmortem last December, Super Win had a bad launch. Its day one sales were a fraction of what I’d hoped for. Now I’m ten months further out, and the game’s been discounted several times and given a major update and a permanent price drop, updated, and I have more data.

To be clear, my initial impressions of Super Win were not wrong. It started out badly and it never really recovered. There was no miraculous event that suddenly pulled it out of obscurity. It’s continued to trend in accordance with those first few weeks. It’s consistently performed about a tenth as well as Eldritch, which was my only real point of comparison at the time of launch. I had numbers from the Steam launch of You Have to Win, too, of course, but free games are so disproportionately popular relative to paid games that it was not meaningful in any way.

The mistake I made last year was in assuming Super Win was failing relative to everything else on Steam. Subjectively, yes, it failed to perform as I would have liked. But in contrast to the rest of the market, it’s right on par. It’s near the median. And that’s what I didn’t know — couldn’t have known — a year ago. I have SteamSpy to thank for that. SteamSpy was a revelation. Suddenly I wasn’t the odd one out whose game tanked. The market just didn’t look the way I thought it did.

So let’s talk sales figures. In twelve months, Super Win the Game has sold 7,640 copies across Steam, Humble, itch.io, IndieBox, and direct sales, with an average unit price of $4.98, generating roughly $38,000 of gross revenue. By my napkin math, this translates to about $18,500 after-tax earnings for my household.

That’s not amazing, but it’s not nothing either. Alone, that’s not quite enough to pay rent, much less completely cover the cost of developing another game, much less actually turn a profit. But in conjunction with my remaining savings, income from contract work, additional revenue from Eldritch, and my wife’s income, we’re staying afloat.

That raises a question. Is it possible to be sustainable at this scale? Is it possible to stay in business without ever having a smash hit? How many games would I have to have in the market simultaneously to reach that point? I’m guessing not too many. Two of Super Win would pretty much carry me. Now obviously it depends on countless other factors, and it’s hard to know for sure what the tail for Super Win will look like in year two (I’m guessing, you know, one-tenth of Eldritch‘s), but I’m optimistic.

Mac and Linux account for about 10.25% of sales (6.25% and 4% respectively), so again by napkin math, I would estimate I’ve earned roughly $1,900 on those platforms. They continue to be a net loss for now. Reaching profitability isn’t totally outside the realm of possibility, however, since there is minimal cost involved in supporting them now that the core engine work is done.

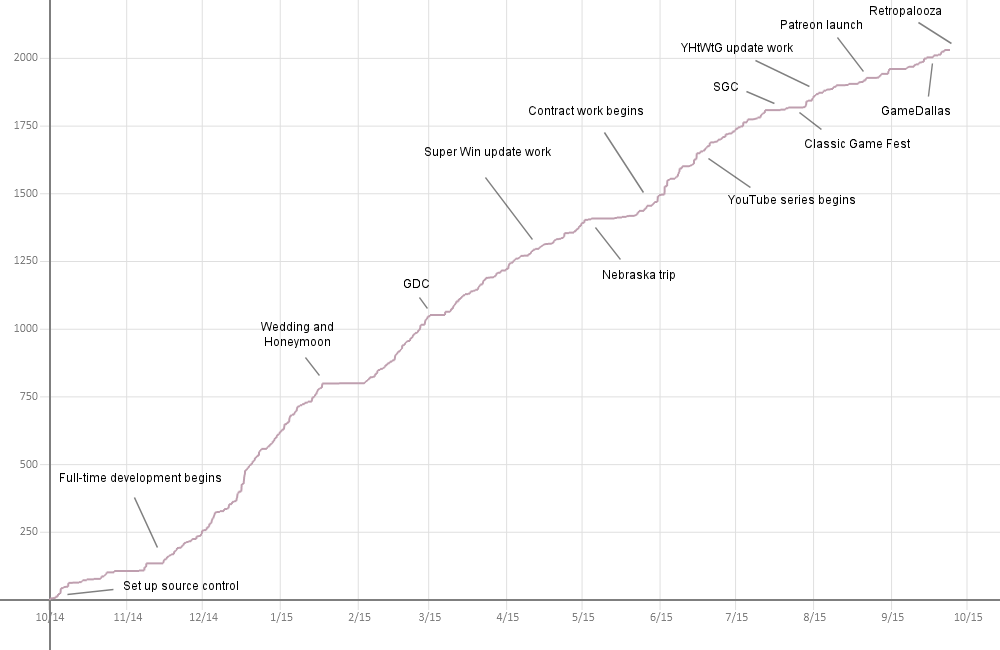

Let’s look at some pictures.

This is a graph of Steam sales over the first year. It shouldn’t be surprising to anyone; it’s a well known fact that games sell the most when they’re on sale. The in-between bits aren’t totally flat, but to provide some sense of scale, on average Super Win has been selling about 50 units per month when it’s not on sale.

The y-axis on this graph is units, not revenue. (If it were revenue, every peak would be lower by the sale percent specified, with another 35% or so chopped off after the price drop.) What’s interesting to me is that it wasn’t until I discounted Super Win by 75% that it matched its launch day in terms of units, and it’s never matched it in revenue. Even in a crowded, sales-driven market, launch day is still the biggest day of a game’s life.

Now that the game’s been out a year, I’ll be looking into bundling opportunities. I know that market has become more saturated than it once was, just like every part of indie games, but I’m hopeful I can find some additional revenue there.

A few months ago, when I announced Gunmetal Arcadia Zero, I talked about the motivation for that game primarily as a way to alleviate a production bottleneck created by ongoing obligations. But it does serve other purposes, too. I can finish Zero faster than I could finish the flagship game, which means I can get something else out into the market, something else generating revenue. But that’s a double-edged sword. Although it can start recouping costs and create awareness for the roguelike game, it also has the potential to diminish interest and harm the chances of Gunmetal Arcadia succeeding if it’s not a quality product itself. So I’m motivated to make Zero the absolute best game it can be.

Zero will be an experiment in other ways, as well. I’ve shared my thoughts on the pricing of Super Win before, eventually culminating in a price drop to better match consumer expectations and allow me to price Gunmetal more appropriately relative to that game. But Zero is a little more of a wildcard, and it’s an opportunity to swing hard the other way and deliberately price a game too low. I’m no fan of the race-to-the-bottom pricing seen on the App Store (and recently in the PC space, as well), but I’ll happily jump at a low-risk opportunity like this to see how a game fares at that point.

A few weeks ago, Daniel West’s “‘Good’ Isn’t Good Enough” blog hit Gamasutra. It’s one in a long line of blogs and articles recently that have given rise to discussion of an “indiepocalypse” in which there are so many games being released every day that none can stand out and succeed.

When I wrote my first postmortem of Super Win last year, the term “indiepocalypse” had not yet been coined (to my knowledge), but there was already a feeling of overcrowding. Greenlight titles were no longer announced with excitement but merely quietly given approval en masse. Games were disappearing from the front page of Steam within a day. It was a stark contrast from even just a year earlier. (And indeed, SteamSpy has noted that October 2013 is when the proverbial floodgates opened. Eldritch was right on the cusp, having been released that same month.)

Daniel West’s blog resonated with me because it recalled many of the elements of my own previous postmortem — importantly, that doing things “right” or being “good” (and I should emphasize the heavy quote marks around those terms, subjective as they are) aren’t a predictor of success now, if they ever were. And the more I learn, the less I think they ever were.

So here’s my hot take. There is no indiepocalypse. There are no games that are failing today that would have been huge successes a year ago. Yeah, it’s maybe conceivable that Super Win would’ve sold a little better if it had been released in 2012 or 2013, but it’s even more likely it wouldn’t have made it to Steam at all. There was a notion for a while that being on Steam was a predictor of success, and that’s probably true, but being on Steam was also a mark of being not only a high-quality game but also one with mass appeal.

Super Win the Game is a high-quality game (and you can fight me irl if you disagree), but it has niche appeal. As a retro pixel art platformer, it also exists in a space occupied largely by many, many games of wildly varying levels of quality, all vying for that same niche market. That’s not a good place to be. Good thing my next game is such a radical departure— oh wait

I guess that’s a fair question, and a place to shift gears and talk a little more about Gunmetal. Why, in the face of middling sales and unforgiving odds, would I choose to make another retro pixel art (action-adventure) platformer?

The truth is, I very nearly didn’t. Even though I launched this blog prior to Super Win‘s launch, I had been taking notes on another game simultaneously, a project by the codename “Cadenza” that I’ve been wanting to make for a very long time. When Super Win fizzled, the whole retro thing felt poisoned to me for a little while, and I was briefly convinced I needed to do a 180 and make something completely different. But clearer heads prevailed, and I decided that it would be better to take the time and effort that I had put into developing tools and tech for Super Win and reuse those for another game, while pushing the bar higher wherever I could.

That’s been the driving force throughout Gunmetal‘s development to date: I have to do better than Super Win. I can’t make something I’m going to be embarrassed to show off. It’s impossible to say whether that will be enough to put it ahead of Super Win in terms of sales, but already, I feel so much better about where Gunmetal is in terms of providing a rich, expressive gameplay experience. I get excited whenever I see animated GIFs of my own game. That’s a good place to be.

I would also add, as long as we’re considering the realm of all possible projects that could have been my next, that I had to narrow it down to something that (1) I was capable of making (2) in a reasonable amount of time (3) with the tools I have available to me, and, perhaps most crucially, (4) it had to be something I wanted to make. There is no room for passionless work in solo indie dev. So yeah, maybe the pixel art platformer is an overcrowded genre, but if I care very deeply about this pixel art platformer in particular, I know that I can finish it and that it will be something special.

I guess that roughly concludes the scribbly line connecting Super Win to Gunmetal Arcadia. Let’s talk about how that’s gone this last year.

One year. I’ve been working on this game for an entire year now. That’s longer than I’ve ever worked on any solo project ever, but then this is a bigger game than any other I’ve ever made. And I’ve barely scratched the surface.

I’m a little surprised I’m not burnt out or jaded toward the concept yet. I’m still excited by the promise of what Gunmetal Arcadia will be. I think a lot of that is due to having had very little time recently to actually work on the game, so in some regards, it still feels like a future project that I’d like to take on someday, when I have the time. That’s weird.

I think that’s indicative of how the development process has been trending, though. After a sputtering start (Gunmetal commenced just as I was moving to a new apartment, and it was some time before I really felt like I was 100% on development), I had a few solid months in which I laid a lot of the groundwork for what Gunmetal Arcadia has become and will become. Reading back through the archives, many of the recognizable aspects of the game were already in place by February. And since then, things have been…spotty.

I kind of just want to let that image speak for itself.

I made a gamble in early July that the time cost to produce a weekly video series would be mitigated by the increase in visibility and ultimately in sales. I won’t know for sure whether this has paid off until the games launch, but I’m optimistic. In the meantime, I’ve spun up a Patreon campaign to support this non-development documentation work.

The future remains as busy and unpredictable as ever. My contract work period is drawing to a close, but I have more obligations on the horizon. I’ve submitted a talk for GDC 2016, with slides due in the coming months, and oh yeah we’re expecting a child in November so that’ll probably shake up my schedule just a bit.

But hey.

I’m still making games.